Late last year, I received an email from the Czech Republic. It contained an invitation from a total stranger. The sender, Michal Holy, explained that a memorial was to be unveiled to four men who had been secretly executed near the northern town of Most. The men where my uncle, World War II fighter pilot John "Willy" Williams, and three other Allied air force officers.

Willy was shot down by friendly fire in 1942 in the Western Desert and sent to Stalag Luft III, near Sagan (now Zagan, Poland), 160 km south-east of Berlin. Ironically, the Nazis thought fencing the “best and brightest" Allied air force officers in one custom-built compound would thwart escape at tempts; instead it proves a remarkable opportunity for them to pool their extraordinary talents and plot. Inside Stalag Luft III, Willy is appointed the chief carpenter and supply officer for a mass escape via a hand- dug tunnel. Its code name is “Harry." He is responsible, among other things, for sourcing and fitting the thousands of bed boards and wooden planks used to shore up Harry.

It has taken Michal almost a year to find us all, and he has used his own money to help pay for the memorial stone, a beautiful piece of rich red polished granite. It's carved by hand with the insignia of the men's squadrons, along with their names and ranks. Michal and Jan and some friends have installed it in the cemetery on a hill overlooking Most. It is here the families gather before we leave to travel north to where it all began.

The first stage of the escape goes surprisingly well. After slogging through the forest, Polish RAF Flight Officer Jerzy Mondschein purchases 12 train tickets south without arousing suspicion. His German is flawless. His daughter, Margaret, has told us she still remembers his letters home. " 'Eat up and stay well, so you will be strong and healthy when I get home,' he used to tell me." Jerzy was on his way.

Official Military portrait of John

"Willy" Williams on joining the

RAF officers' program,

December 1937.

Michal, a commercial pilot and amateur historian with no direct connection to any of the dead men, was attempting to contact relatives of all four, hence the email that found me, my brother Richard and my mother. Michal wanted us to attend the unveiling, and then to join him in a very special journey. He planned to retrace these men's fateful last days on the run in Nazi controlled Europe. Their extraordinary exploits beginning with an audacious mass escape from a prisoner of war (POW) camp along with dozens of other officers had been celebrated in books, film and WWII folklore. Many know it best through the movie version The Great Escape (1963) staring Steve McQueen. But the real Great Escape was just as heroic and ultimately more tragic than Hollywood dared portray.

Why now, I wondered, nearly 68 years after the event? Like most of the surviving relatives of the escapees, Michal was far too young to remember the Nazi era. But, having stumbled across details of a brutal crime that had been committed near Most (then called Brux), he and his friends had vowed to do what they could to make amends.

I was stunned by the invitation at first. News of Uncle Willy's death had profoundly affected my dad, his youngest brother, and had devastated my grandparents and the wider family. As I grew up, I felt his ghostly presence. For years Dad took us, rain or shine, to swim at Manly, the Sydney beach where he had surfed with Willy before the war. But it didn't take long for me to realize that this invitation was a wonderful opportunity, not only to understand what really happened, but to finally help afford Willy the dignity and recognition he'd so long been denied.

A lifetime ago, Willy is believed to have been pushed out of a car into a lonely forest in Czechoslovakia by his Gestapo guards and shot in the back, or the back of his head. How a young Australian perished so deep behind enemy lines was part of sensational war story, and perhaps a visit to the Czech Republic could help me fill in the details. Along with my mother and brother, I told Michal we would be thrilled to accept his invitation.

In the movie The Great Escape, Steve McQueen's character, Captain Virgil "The Cooler king" Hilts survives the Nazi manhunt that followed the mass break-out of Allied airmen from the notorious and supposedly "escape proof" POW camp, Stalag Luft III. The film's characters are composites of the real men but many of the details of the escape are accurate. (The famous motorcycle chase, however, never happened; it was dreamed up by McQueen himself). The real life version goes something like this.

Steve McQueen as American POW

in The Great Escape.

On the night of 24-25 March 1944, my two hundred Allied airmen arrive in timed intervals at Hut 104 inside Stalag Luft III. They are disguised as businessmen, migrant workers, and there are even a few ersatz German soldiers. For a year or so, a massive operation has gone undetected by the German guards. Shifts of prisoners have been secretly digging and excavating an escape tunnel, 102 metres long and roughly 9 metres below ground level.

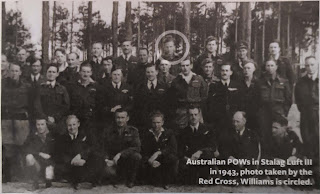

Australian POW in Stalag Luft III in 1943,

Photo taken by the Red Cross,

Willian is circled.

My uncle is a 24-year-old Royal Air Force (RAF) Commanding Officer; the air war had exacted a heavy toll on both sides and fighter pilots advanced alarmingly quickly through the ranks. Willy had earned a Distinguished Flying Cross fighting the "Desert War" over Libya and Egypt, flying in decidedly nonregulation baggy khaki shorts and sandals, and had a reputation as a clown. However, his weekly letters home, which my grandmother clung on to until her death in 1957, suggest a resolute and analytical young man behind the loutish grin.

Willy was shot down by friendly fire in 1942 in the Western Desert and sent to Stalag Luft III, near Sagan (now Zagan, Poland), 160 km south-east of Berlin. Ironically, the Nazis thought fencing the “best and brightest" Allied air force officers in one custom-built compound would thwart escape at tempts; instead it proves a remarkable opportunity for them to pool their extraordinary talents and plot. Inside Stalag Luft III, Willy is appointed the chief carpenter and supply officer for a mass escape via a hand- dug tunnel. Its code name is “Harry." He is responsible, among other things, for sourcing and fitting the thousands of bed boards and wooden planks used to shore up Harry.

Willy's schoolboy German allows him to beg the guards for the odd supervised stroll "outside the wire," where he can survey the terrain. When he is allocated his place-number 31-in the escapee line, his role is to lead the next 11 men out and onto a German train south. His group is to aim for Switzerland via German-occupied Czechoslovakia, where they hope to make contact with the Resistance.

Two hundred men wait for their turn to crawl on their elbows through the dank, narrow tunnel. But when the dark, moonless night they need finally arrives, unseasonal snow and an Allied air raid slows the queue down. Only 76 men make it "out of the bag" before a guard spots an escapee and sounds the alarm.

John Williams, 1935,

Manly Swimming Club,

New South wales champion

team; (below) with his

p-40 Kittyhawk in

Africa, circa 1942.

Michal guides our minibus as it pulls into the ruins of Stalag Luft III. On board are a handful of relatives, a Czech and an Australian TV crew, and several military experts. We are fresh from the unveiling of the memorial in Most; a moving formal ceremony complete with Czech honour guard and air force fly-past. I am astounded to stand alongside other families, with diplomats, military officers and even aged local Czech survivors of the war, to pay our respects.

All our lives we've heard versions of what happened on the fateful night. But then all of a sudden we are standing together on the exact spot where the men emerged into the freezing night to discover their tunnel was just short of the cover of the forest. Each escapee was momentarily exposed as he scrambled out; the remains of the guard tower make that point abundantly clear.

A couple of years ago, Michal tells me, he didn't know much more about the Great Escape than what he had picked up from the film.

But then, while helping friend Jan Zdiarsky, founder and director of an aviation museum, to research a WWII air battle that left the Czech Ore Mountains littered with downed US aircraft, Michal made a visit to Stalag Luft III. The US pilots who survived being shot down were imprisoned there.

He recalls that it was about zero degrees and there was nobody around. When he started to walk through the woods in the camp he became deeply affected by a strong sense of the courage and determination of those men.

A Gestapo picture of Williams in his

escape garb after his capture.

Michal immediately put his work on the US POWs on hold as his interest turned to the British POW compound where the escape plot was hatched.

When Michal discovered that some escapees had been executed in what is now the Czech Republic, he decided it was a trail he needed to follow. And, extraordinarily, that led to a thick dusty file that he dug out of the National Archives back in Prague that had been overlooked for decades. Inside were the original Gestapo cremation orders and post mortem records for the "Most Four": Willy; his escape partner and old school friend, Royal Australian Air Force Flight Lieutenant Reginald "Rusty" Kierath; British RAF Lieutenant Leslie "Johnny" Bull; and Polish RAF Flight Officer Jerzy Mondschein.

As an Airbus pilot for Czech Airlines Michal understood that these young WWII fighter pilots were extraordinary; with only a few hundred hours of flying experience, men were sent into combat, forced to fly and shoot at the same time, while evading enemy fire.

And yet, there was nothing to mark where these four young pilots had died, and nothing solid to honour their memory.

But, as I stand in the forest, I can't help but wonder why a group of strangers in a nation that had suffered hundreds of thousands of its own causalities during the Nazi occupation and the austere Communist era that followed - every single individual loss just as important as ours would single out the "Most four"?

Michal explains it to me like this: "It's something which should have been done many years ago. It was like we [Czechs] had a debt to pay to the families of the men. This was deliberate, calculated murder, not death on a battlefield in war."

It has taken Michal almost a year to find us all, and he has used his own money to help pay for the memorial stone, a beautiful piece of rich red polished granite. It's carved by hand with the insignia of the men's squadrons, along with their names and ranks. Michal and Jan and some friends have installed it in the cemetery on a hill overlooking Most. It is here the families gather before we leave to travel north to where it all began.

From Left: Czech pilot Michal Holy; the

memorial at Most; Richard and Louise Williams

at the memorial ceremony.

Standing in the cold in the spot where the tunnel ended, I could finally put myself in Willie's place: the sheer joy of the moment, relishing the freedom of being on the other side of the barbed wire. Over the years, I've read several first-hand accounts of the moment the men emerged. And then some years ago I spoke directly with RAF Squadron Leader Bertram "Jimmy" James, who was in Willy's escape group. It had been snowing that late March of 1944-an unseasonal cold snap even for Central Europe. The cold, Jimmy had said, cut through them like a knife. As they headed off into the woods, a couple of jumpy escapees thought they heard sounds. Willy assured them that no one but other "kriegies," the nickname for POWs, would be out in the dark, But the snow crunching underfoot still seemed to make enough noise to wake dead.

Behind Willy was Rusty, a close friend from school. Now, beside me, Rusty's nephew, Peter, is riding the same roller coaster of emotions as I am. But we are also both realizing a deeper appreciation of the courage, determination and ingenuity it took to make it out.

The original POW compound is huge. There's the reservoir, apparently used by POWs for unauthorized skinny-dipping in summer and large enough for a strong surfer like Willy to race across. Then there's the theatre built by the POWs, with a void to hide the sand excavated from the tunnel, and exhibitions detailing the numerous sports matches and contests. Despite the physical deprivations, the POWs were determined not to let their spirits break behind the barbed wire.

I am humbled as I step inside the replica of Hut 104, reconstructed by the RAF in the men's honour. This is where the tunnel began. Willy's face, and the face of every man executed, stares out at us from the wall. We can feel the sheer determination and drive in their gaze.

The first stage of the escape goes surprisingly well. After slogging through the forest, Polish RAF Flight Officer Jerzy Mondschein purchases 12 train tickets south without arousing suspicion. His German is flawless. His daughter, Margaret, has told us she still remembers his letters home. " 'Eat up and stay well, so you will be strong and healthy when I get home,' he used to tell me." Jerzy was on his way.

A guard tower, Stalag Luft III, circa 1942.

It is a long, slow, nervous ride. But when the train reaches its final stop at Boberröhrsdorf, the Czech border is in distant sight, over the snow covered mountains. Of the 12, only Willy, Rusty, Jerzy and Leslie decide they can make it across on foot.

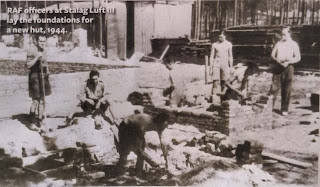

RAF Officers at Stalag Luft III lay the foundations

for a new hut, 1944.

On any other occasion this would be a magical journey. Our minibus winds around the mountain bends, at every turn a perfect picture postcard of snow, mountain chalets and fir trees bathed in spring sunshine comes into view.

But it must have been a near impossible trip for the escapees. When we stop at the border, every step is a hazard and we are soon thigh deep as the soft snow collapses underfoot. We know the spring melt forced the men back onto the road where they were most at risk. Somewhere near the spot we are standing, the four men are intercepted by a German alpine patrol.

Willy, Rusty, Jerzy and Leslie have survived the air war. They have survived being shot down. They have survived as POWs, often with little food and in terrible cold. They have survived the construction of an almost impossible tunnel and they have made it to the Czech border, the last 20 or so kilometres on foot.

The 76 escapees are officers and see it as their duty to escape. They have diverted the efforts of thousands of German troops and police to the manhunt, causing the "maximum disruption" anticipated in the Allies strategic handbook. Their mission, then, has been a remarkable success. The rules of engagement now require the Nazis to dispatch them back to a POW camp.

But this escape so humiliates Hitler that he flies into a rage and orders the execution of every one of the 73 POWs that have been recaptured. According to first-hand accounts that emerge after the war, some of Hitler's advisors counsel him against the murders; it is a blatant breach of the Geneva convention and will certainly draw ferocious Allied reprisals. A compromise sets the death list at 50. Willy, Rusty, Jerzy and Leslie are on the list.

I have always felt a great responsibility to honour Willy's wife. My father, Owen, died in 1989. When my uncle, David, the longest surviving Williams sibling, passed away in 2006, I became the custodian of Willy's story.

There was something incredibly poignant about the modest cardboard box of Willy's personal belongings and the pile of fraying clippings and document passed down to me by Uncle David. I had Polished the small silver surfing trophy Willy won in the summer of 1935 as a member of the Australian champion junior surf boat crew and the silver school napkin ring for athletics. I even put them both on display at my home in Sydney.

What happened after the four men were recaptured is partly conjecture. But the Nazis were obsessive record keepers. The orders for the crematorium that Michal found in the same file as the post mortem records claimed they had been shot "trying to escape" their guards, but a close examination of the dates shows that they were signed by the Gestapo before the escapees were killed.

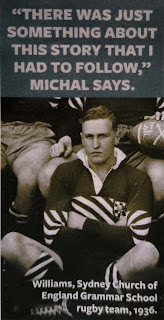

"There was just something about this story that I had to follow," Michal says.

In our bags we now had the closest thing to a complete dossier, including declassified British intelligence documents about the escape and haunting, final "mug shots" of the men taken by the Gestapo.

Sixty-eight years is a long time. Of the family members who had gathered in Most on 24 March 2012, on the anniversary of the escape, many had come carrying someone else's grief. My grandmother never recovered from Willy's death. She became chronically ill and sought out her eldest son at séances, as did many bereaved mothers of the era. For me, and my brother and mother, it is such an honour to attend the memorial ceremony; it is the funeral Willy never had.

I spend a long time trying to work out how to thank Michal for seeing it through, from the discovery of the cremation orders to such a magnificent day in the sun in Most. So many local people came, and brought with them such pure good will. I will never forget their kind faces and the reception; every cake, strudel and sandwich homemade.

After the ceremony and surrounded by well-wishers, Michal presented a hand-made plaque to the family members of the "Most Four" who have made the special trip back to Most. On each plaque, he and Jan and their friends have etched the dates 24 March 1944 and 2012, and a drawing of Stalag Luft III. Behind a small glass pane, there is a pinch of sand, with this engraving: "This sand was dug up and removed during the construction of the tunnel Harry, which should have led the men to freedom."

It sits on my desk, just to the left of my keyboard, where I can look at it every day.

An eyewitness account from a young Czech suggests they were last seen alive in the Gestapo cells in the town of Liberic (then Reichenberg), the building now an unassuming bank. As with the other executions carried out on the escapees from Stalag Luft III, the four were then driven the considerable distance to be executed near Most-perhaps because there was a crematorium there.

I had always hoped that willy has died with his friend Rusty, and that he had not known he was being taken to be killed. But after reading accounts by Paul Brickhill, a fellow Stalag Luft III POW who wrote the original book on the escape, I now know that of the four, it may have been only Willy who knew they were being driven to their deaths.

After the war, war crimes investigation into the Great Escape execution resulted in 20 former Gestapo officers being sentenced to death and the jailing of many more. No one was brought to justice for the execution of the Most Four and, until now, the events leading to their deaths have been unclear.

In our bags we now had the closest thing to a complete dossier, including declassified British intelligence documents about the escape and haunting, final "mug shots" of the men taken by the Gestapo.

Sixty-eight years is a long time. Of the family members who had gathered in Most on 24 March 2012, on the anniversary of the escape, many had come carrying someone else's grief. My grandmother never recovered from Willy's death. She became chronically ill and sought out her eldest son at séances, as did many bereaved mothers of the era. For me, and my brother and mother, it is such an honour to attend the memorial ceremony; it is the funeral Willy never had.

I spend a long time trying to work out how to thank Michal for seeing it through, from the discovery of the cremation orders to such a magnificent day in the sun in Most. So many local people came, and brought with them such pure good will. I will never forget their kind faces and the reception; every cake, strudel and sandwich homemade.

So I think about my dad and the two things he had always kept close to him; a beautiful sepia portrait of his young, smooth-faced brother going off to war, and Willy's RAF wings. I present Michal with our gift at dinner with our unusual tour group after the long, emotional day at Stalag Luft III. Now, in Michal's home in Prague, hangs a framed sepia portrait of Willy and a set of his RAF wings.

Before I left Australia I had gone down to Manly, where my father's family had lived, and where the Williams boys had surfed, and filled a small container with Manly beach sand to Scatter around the base of the memorial at Most.

After the ceremony and surrounded by well-wishers, Michal presented a hand-made plaque to the family members of the "Most Four" who have made the special trip back to Most. On each plaque, he and Jan and their friends have etched the dates 24 March 1944 and 2012, and a drawing of Stalag Luft III. Behind a small glass pane, there is a pinch of sand, with this engraving: "This sand was dug up and removed during the construction of the tunnel Harry, which should have led the men to freedom."

It sits on my desk, just to the left of my keyboard, where I can look at it every day.

- Louise Williams

Comments

Post a Comment